Am I doing strength all wrong? According to leading endurance sport physical therapist and running form expert, Jay Dicharry, I probably am.

“For most triathletes, you’re doing it wrong,” he says. “When I was in the best shape of my life, I was swimming like a swimmer, cycling like a cyclist, and running like a runner. And I lifted in the gym with college linemen.”

“Unfortunately, people approach the sport of triathlon with a fit-it-all-in mentality, so you do an average job at all three sports. But what if you could do a great job at all three with less volume?”

Now, let’s be clear. Jay isn’t saying that everyone needs to be lifting like a football player. He’s talking about being intentional with strength work instead of just “fitting it in” when you have time.

Do you place the same level of importance on gym work as you do your swim, bike, and run workouts? I don’t, and I actually do strength twice a week!

I get it. It’s hard to juggle swim, bike, and run workouts and then add strength work on top of that (in addition to work, family, life, ect.) Jay’s point is that the benefit of strength and mobility work isn’t just to prevent injury, rehab from injury, or even build more powerful muscles, although that’s good too.

The reason triathletes should do strength and mobility work is to improve our swim, bike, and run performance by building better body parts and learning how to move those body parts correctly.

Let’s back up for a second so I can tell you a little about Jay Dicharry.

He’s a board certified sports clinical specialist who has a long history in gait analysis. He was the former director of the Speed Lab at the University of Virginia that has recorded biomechanics data from over 7,000 runners.

Now, he works at the Oregon State University biomechanics lab. He’s worked with over 50 Olympians, as well as Ironman Champions like Heather Jackson, and he’s the author of multiple books.

That’s how I had the opportunity to chat with Jay. His new book- Running Rewired: Reinvent Your Run For Stability, Strength, and Speed, 2nd edition, was just released in March 2024.

The book includes 11 self-tests for mobility, posture, rotation, and alignment, 80 different exercises, and 16 workouts that teach you how to move with more precision and power.

A big focus for me this year is running, and Matt’s still working to come back from an injury, so strength is really important for both of us to incorporate into our weekly training. But sometimes it’s hard to figure out which exercises will best translate to the sport of triathlon.

That’s why I invited Jay on the blog- to pick his brain about strength for triathletes, posture drills, foot strike, how to really do plyometrics, and much more.

Author’s Q&A with Jay Dicharry

Brittany- Why did you write this book and what do you hope athletes learn from it?

Jay- “There’s so much noise out there. You open up Instagram and there are videos like, ‘3 Exercises Every Runner Needs to Do!’ and it’s not helping anyone.”

“The biggest problem I see isn’t in the engine, but how you build your body parts. If I asked the question: How do I build stronger muscles, more resilient bones, and springier tendons? No one is going to say swim, bike and run, because that’s not the best way to build your body parts.”

“People don’t get hurt because they’re not fast. They get hurt because they don’t spend the time to build their body parts correctly. You need to put in the time to do that each week.”

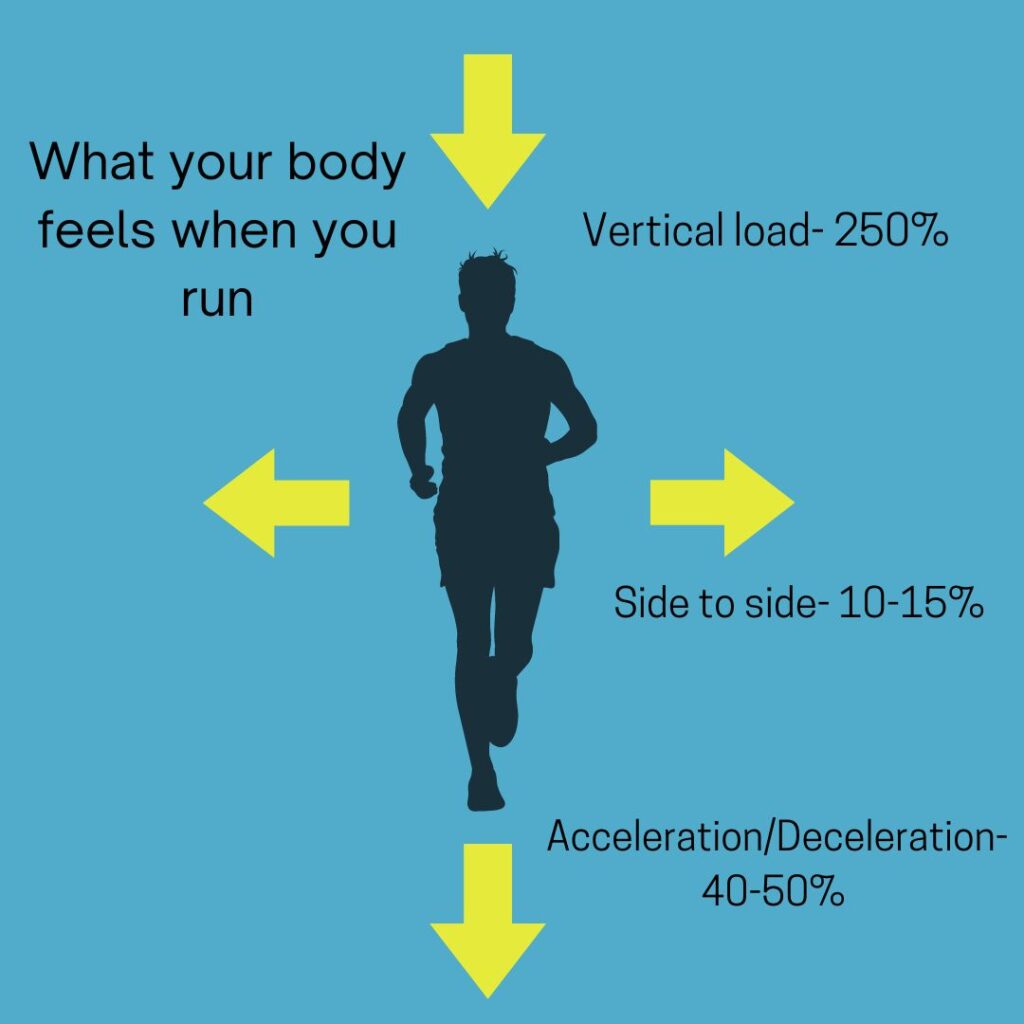

If we’re talking about the sport in which a triathlete is most likely to get injured, it’s probably running. There are a variety of reasons why this is the case, but the biggest culprit is the imbalances we all have that don’t allow us to move correctly.

Did you know that running is a single-leg sport? In the book, Jay explains it this way.

When we run, the body must deal with 2.5-3 times its body weight with every stride. So if you stand on both legs, your weight is divided with 50% on each leg. Now, stand on one leg (which is what you do when you run) and you’re supporting 100% of your bodyweight. Now, hold a barbell with 150% of your body weight and stand on one leg. That gives you an idea of what your muscles, tendons, and bones must support with each and every step, for miles.

So what should we do? Build bigger muscles with squats and leg extensions? Not exactly. That will build bigger muscles, but we want better muscles.

It’s the difference between intramuscular coordination and intermuscular coordination. Intramuscular coordination is how a muscle talks to itself. This involves using specific, isolated movements that help rewire the connections within the muscle so it fires properly. An example of this might be a single leg split squat.

Intermuscular coordination is how muscles talk to each other. You could do leg extensions all day to build quads that rival those of a body builder, but fixing that one muscle won’t help you run any better.

“In sports, muscles don’t act in isolation the way they do on a leg extension machine. You need to train movements, not muscles,” Jay says.

In the book, Jay provides an example of a runner whose external hip rotators were “unplugged.” The muscles weren’t firing so he wasn’t able to use them while running. This was a problem because it made his knee collapse, which made his IT band very angry.

He started doing isolated movements to help rewire the brain-body connection, which took a lot of mental concentration, and he didn’t always get it right. This was the cognitive phase.

After 2 weeks of doing the exercise, his movement was getting better, but it still took some thought. That’s the associative phase.

A month into doing the exercise, it had become easy and automatic. His muscles were firing properly, and he could incorporate the movement into his running gait. That’s the autonomous phase- when the movement and engagement of muscles becomes automatic.

Here’s an excerpt from the book.

“Coordination, control, and precision are all skills that every runner needs to practice. These movements require high volume and little resistance. These skills should be practiced a couple of times every week, all season long, to ensure that the movement skill can be put to use while running. You need to own the movement. Not just in an exercise or drill, not just at mile 1, not just at mile 5. But at every repeat of your track workout, every hill effort, and every mile of your race. The end goal is to make that refined movement awareness reflective.”

Brittany- We’re not just runners. We’re triathletes who have to swim, bike, and run multiple times a week. It’s hard to fit in strength too. What’s the ideal frequency and duration of strength workouts for triathletes?

Jay– “Endurance athletes tend to go to the gym in a rush, just to get it done. You need to push your body in the gym the same way you push yourself in an interval workout. Don’t just go through the motions.”

“Everyone is looking for the new exercise of the week, but you just have to get really good at fundamentals. The vast majority of folks 30 and over can do the three performance workouts I have in the book and cycle through those forever.”

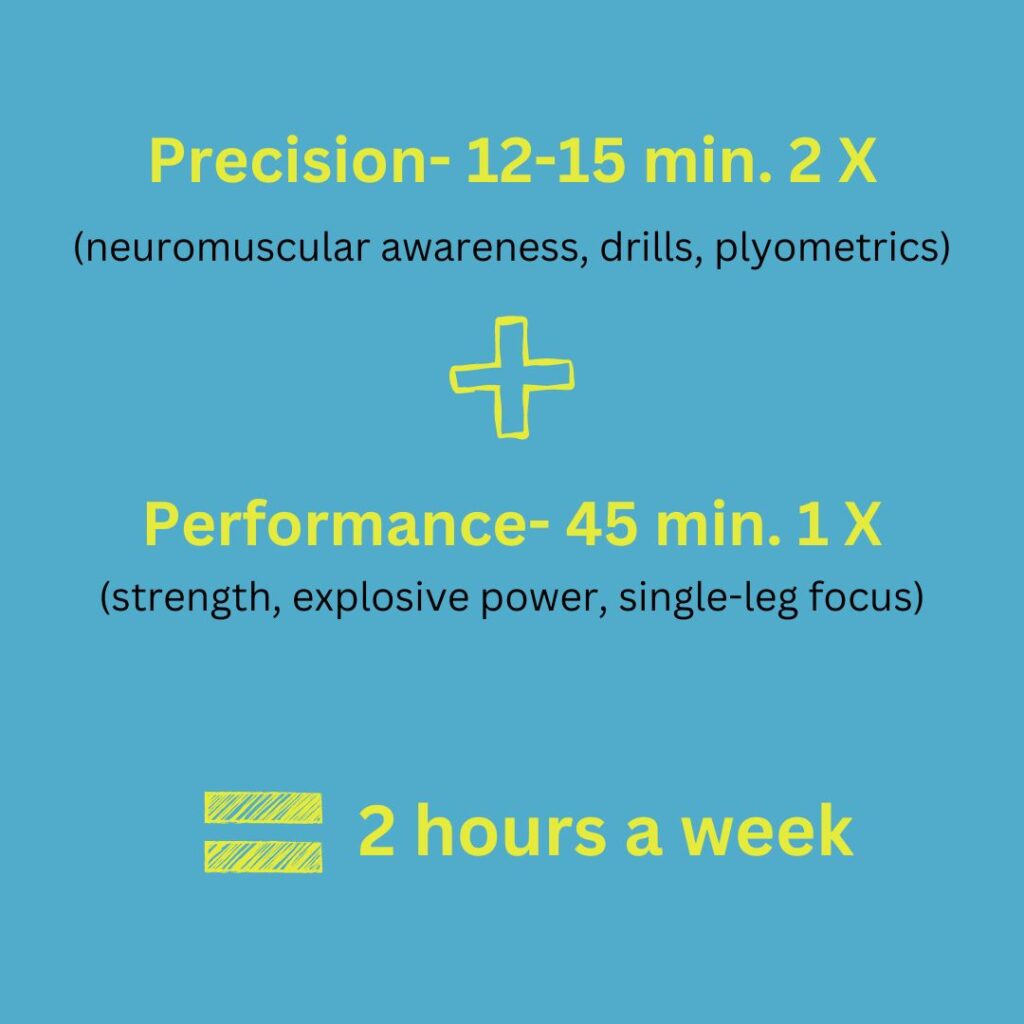

The workouts in the book are divided into sections.

- Drill Work with stride mechanics and plyometric drills. These can be done before, during, or after a run.

- Prehab Workouts for bone and tendon loading

- Precision Workouts with core, hip, and calf focus

- Performance Strength Workouts with single leg focus, horizontal force, and vertical force

The drills and precision workouts focus on neuromuscular awareness. Jay says these are great to use as a dynamic warmup before you swim, bike, or run. They only take 12-15 minutes per session and we should do them twice a week.

If you’re working on strength for performance, pick one of the 45-min. performance workouts. You do that once a week. If you’re over 40, Jay says there’s a strong argument for doing that twice a week.

“So that’s just 2 hours a week total, and it’s the same for elite athlete too,” he says. “I can tell you about the Olympians and Ironman champions who’ve done this, and it does pay off in spades. If you don’t think you enough time, would I tell someone to skip a run and do one of these strength workouts instead? Without pause, yes.”

Brittany- What about female-specific strength? First we were told we needed to use less weight and more reps, and now the popular thing is lifting heavy?

Jay- “There’s really so much sad stuff done to women in marketing. Let’s be real. The strength needs of a woman aren’t very different from the needs of a man. There’s a definite difference in physical capacity, but when looking at the biomechanics of swim, bike, and run and what you need to build better parts, it’s more about variability between people than differences between genders.”

“Now, there are two things in relation to female anatomy. On average, a woman will have a wider pelvis than the average man. A wider pelvis means you will need more frontal plane or side to side hip stability.”

“The second thing is that the average man has more fast twitch muscle fibers than the average woman. So it would be beneficial for women to have more high intensity and high effort strength and power work than men. That’s how to level the playing field 100%.”

“There are a few methods in the book for explosive power. One day, you might do a squat workout where the focus is on strength, so you use bodyweight or add the bar with some weight. That builds strength. If you want to build power, take the weight off but move faster. So it might be a jump squat with bodyweight or just the bar. Power is force in less time.”

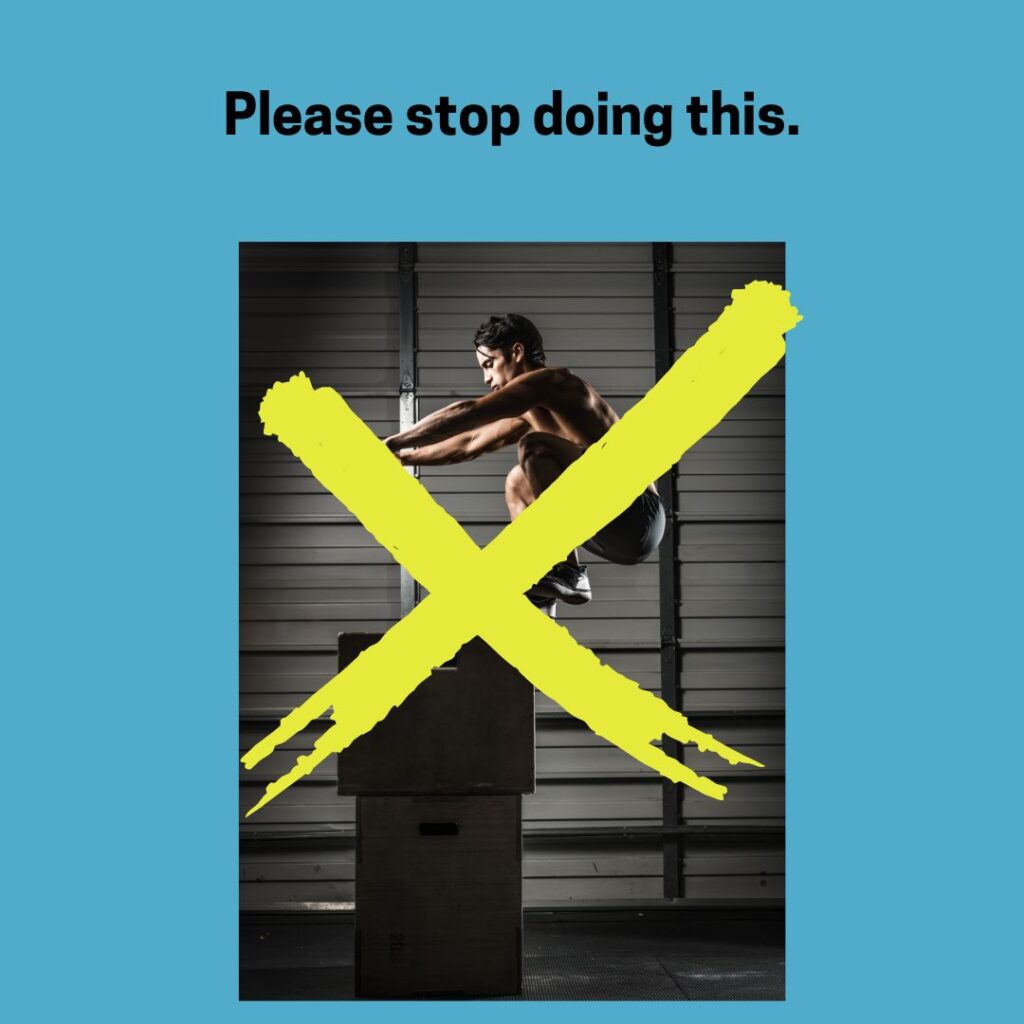

Brittany- That brings us to plyometrics. What’s the best way to incorporate these jumping exercises?

Jay- “Most people do plyometrics wrong. It’s trendy on social media to see a video of someone jumping on top of a box as high as their chest. That’s cute, but it doesn’t translate to your sport. What we need to be better at is getting off the ground quicker and being more explosive.”

“There’s never a reason for an endurance athlete to jump up on a box higher than their chest. It’s just not specific to your sport. The higher the box, each time you jump up, you will spend more than 1/3 of a second sinking deeper into a squat to jump up again. It’s not fast enough. You’re building strength not power.”

“The idea isn’t to jump high, but to jump fast. You can jump up on a box, jump down off a box, do a split box jump, or jump laterally over a box. Basically, when you’re in the air and descending back toward the ground, think about pushing hard to start the drive of the leg for the next jump.”

Brittany- I really like the posture correction drills in the book. What’s a simple thing people can do to improve their running in just 2 minutes?

Jay– “If your goal is to do an Ironman, you need to have good posture at mile 1 and mile 25. You have to build that insight so you know how to keep your boxes stacked.”

“If you’re doing a long run on the weekend and have a bottle stashed somewhere, when you stop to get a drink, take two seconds to maintain body awareness, stack your boxes, and then keep going.”

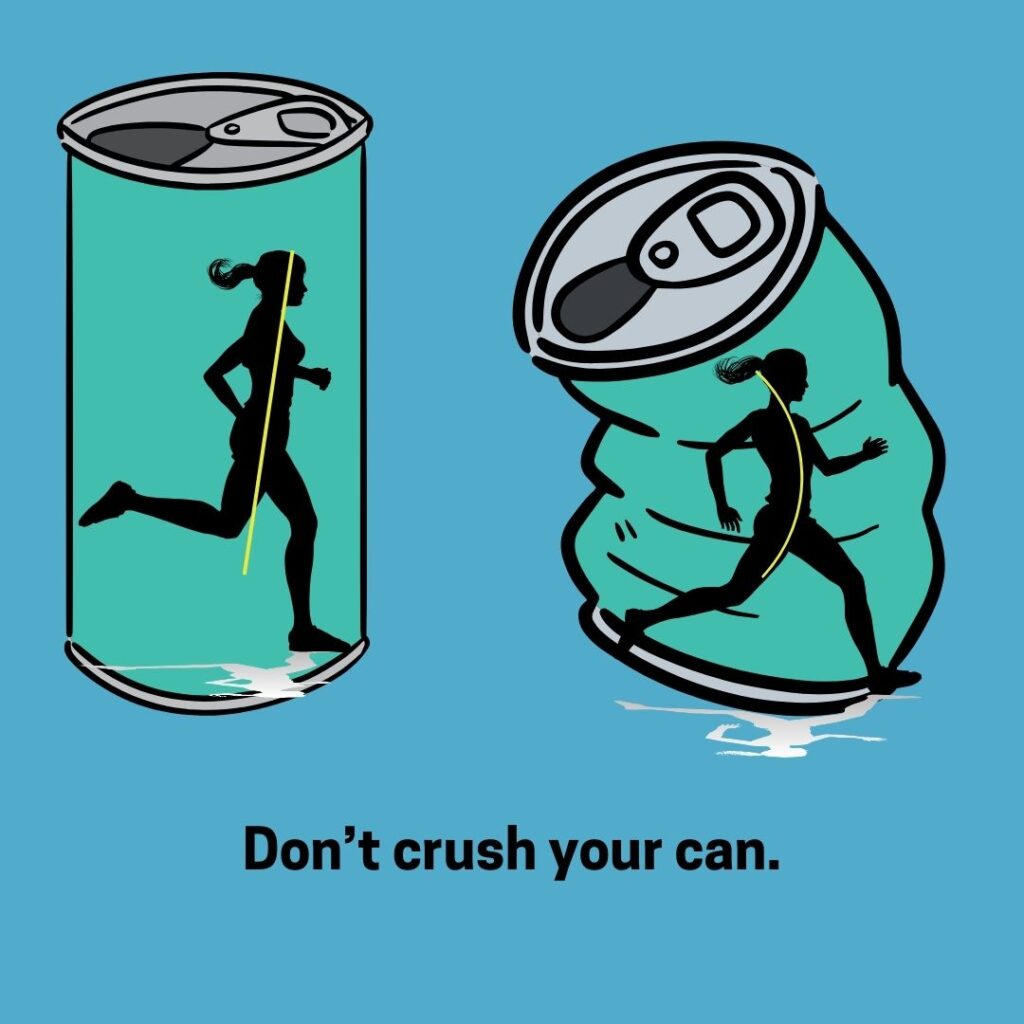

Jay likes to talk about boxes and cans. Basically, it’s a metaphor he uses to describe postural alignment.

Think about an empty soda can. If you place weight on top of the can, it will probably hold up just fine. Now, what happens if you pinch the can so it has a dent? Whether the dent is in the front or the back, when you put weight on top of the can, it will collapse. Your body is the can.

One of my favorite running drills in the book is the Posture Test. You stand with your feet shoulder width apart. Then, think about where you feel the most weight in your feet. (Mine is in my heels.)

Next, put one hand on your belly button and the other hand on your chest. Move the ribcage slightly forward and down until you feel the weight in your feet shift to your midfoot. Let your arms hang by your side, palms forward to screw your shoulders back. Once you’ve found your neutral spine position, stand on one leg and the other. Then, go run.

I tried this on my long run. Whenever I stopped to take a drink, I would reset my posture. I really helped me focus on keeping my spine stacked in alignment to prevent overstriding.

For runners who have issues with overstriding, increasing cadence or leaning forward doesn’t really fix the underlying issue. You have to learn how to activate the right muscles to keep your body in alignment.

I thought his explanation about foot strike was the best I’ve ever heard. It doesn’t necessarily matter how your foot lands on the ground, but where it lands in relation to your body.

As a personal example, I asked Jay about something I struggle with while running. I never really feel like I’m using my glutes. I have pretty significant anterior pelvic tilt (common in females) and little kick back to speak of, so I don’t think I’m using my glutes and hamstrings very effectively.

Apparently, it’s a very common thing. Lab data Jay has collected over a decade shows that a vast majority of runners don’t know how to fully use the muscles in their backside.

So I was directed to the Hip Drive section of the book, which includes exercises like Pigeon Hip Extension, Frog Bridge, Chair of Death Squat, and Single Leg Deadlift with a dowel. I’ve been using a few of them as a dynamic warmup before my last few runs and have already seen a BIG difference in what I feel while running.

“There’s variability in the spine. If you have more lower back curve and pelvic tilt, that’s just you. So, we teach you how to control movement based on your alignment,” Jay says.

I could’ve asked Jay a thousand more questions, but most of the answers can probably be found in his book. Click here to buy Running Rewired on Amazon.

It’s not a leisure read. It’s jam-packed with information and makes you think. It’s part scientific explanation about the mechanics of the body/part strength guide for drills and exercises.

I’ve always been a big proponent of doing strength work. I’ve do it mostly for injury prevention– to ensure I can do the fun things, like swimming, cycling, and running.

But now I’m starting to think about how strength work can improve my triathlon performance. That’s exciting.

“After one day of doing strength, you will get sore,” he says. “But give it 8 weeks and you will see better splits and be recovering faster so you’re not as beat up after a long run. You will be blown away at how you feel.”