A race can be defined as an attempt to get from point A to point B in the least amount of time possible, and there are a number of factors that will determine your success.

Physical fitness, mental preparation, fueling, ect.

But arguably the most important factor is pacing, or the ability to use judgement to make good decisions about how to moderate effort over a specific distance.

There’s a phrase that’s become associated with the art of finding your limit. It’s one that my husband often uses when talking about his pre-race plan…

Empty the Tank.

But the trick is emptying the tank by the finish line and not at mile 12 of your half marathon, so how do we accomplish that?

I had the opportunity to interview Matt Fitzgerald (yes the Matt Fitzgerald!) about his new book: How to Run the Perfect Race: Better Racing Through Better Pacing to see if we could gain some pearls of wisdom about how to become a “pace master.”

Why do we suck at pacing?

But it’s more than that. It also has to do with experience. An athlete who’s been running for 30 years is going to be better at pacing (theoretically) than an athlete who’s been running for 7 years. (Yes, this is an example of me and my husband.)

Another reason is that most runners, and triathletes, have become overly dependent upon technology to do the pacing for us, which hinders body awareness and judgement- both essential skills for pacing.

“The thing to understand about endurance performance is that perceptions don’t just indicate our limits; they are our limits. When you feel you can’t run any harder, you can’t, and when you feel you can, you can- no matter what the numbers say.” – Matt Fitzgerald

Think about this scenario. You’re running, easy or hard, it doesn’t matter.

Can you accurately estimate how far you’ve run, without looking at the GPS on your watch? Hmmm…

Can you accurately estimate the pace you’re running, without looking at your watch? Uhhh…

That’s kind of his point.

But the cool thing is that you can get better at estimating pace, distance, and time, which will make you better at pacing. How? The same way you get better at running, with practice!

“The typical runner recognizes that pacing matters and knows they need to get better at it, yet does little more to improve the skill than vaguely try to get better each time they compete. Mastering the skill requires a more intentional, structured, and sustained approach.”- Matt Fitzgerald

Fitzgerald describes pacing as a democratizing element of the sport. This makes sense because your ability to be good at pacing has nothing to do with speed, talent, or physical ability. You can be a slow runner and be great at pacing.

He says the skill of pacing is based upon three key traits: body awareness, judgement, and toughness.

Body awareness is a feel for your limits, so asking yourself questions like “Can I sustain this effort for the rest of the race” or “Am I feeling how I should at this point in a workout?”

In the book, Fitzgerald suggests a great exercise to develop this ability called body scanning. While running, you focus on a small piece of the experience at a time. But don’t try to change anything; just notice how you feel.

This might include examining your breathing, the rhythm of your arms and legs, tension in your face and shoulders, perception of speed, and contact with the ground.

Time limit estimation, or how long you think you could sustain a certain pace, is another great skill. Within the book, Fitzgerald provides a standardized RPE (rate of perceived exertion) scale with a physiological correlate and corresponding time limits.

It’s a great way to learn what a specific RPE value is supposed to feel like.

For example, a 5/10 is a pace you could sustain for 2:00:00, a 6/10 is a pace you could sustain for 1:00:00 and a 7/10 is a pace you could sustain for 20-30 min.

I thought about this on my 8-mile run last weekend that was supposed to be a RPE of 4/10. During the run, I asked myself if I could sustain my current pace of running for 5:00:00? Most of the time, the answer was no, so I backed off a bit.

Developing good judgement

Developing good judgement, as it relates to pacing, is a common theme throughout the book.

Fitzgerald says the most common mistake runners make is setting workout pace targets based on aspirations rather than a realistic assessment of fitness. Of course, this is easier if you have a coach who can help you with this type of thing.

“Aspirational workout goals inevitably lead to overreaching and frustration,” he says. “Remember to always train as the athlete you are today, not as the athlete you hope to be on race day.”

His most common errors in pacing during a race include:

1. Bad planning or not having a plan

2. Not sticking to the plan

3. Sticking too much to the plan

So you should have a well-thought out, specific plan, and you should commit to sticking to the plan. But you should also have the ability to adjust the plan when needed.

“All too often runners arrive at the start line with a well thought out pacing plan for the race, only to crumple it up and go faster then intended, whether in reaction to the athletes around them, or as a panic response… It’s almost as if the you who plans for the race is different from the you who does the race, a less rational version of yourself addled by adrenaline, stress, and competitive juices.” – Matt Fitzgerald

When determining pacing goals for a race, we should consider pace first and time second. You can do this by using benchmark workouts to define what that means for you as an athlete. (There are several examples in the book for 5K up to marathon distance.)

Then, we have to consider outside influences, like course, terrain, and weather conditions.

Finally, Fitzgerald cautions against being afraid to make a mistake. It’s ok to make a mistake! That’s how we learn, but we have to make a conscious effort to do better the next time, not just repeat the same mistake over and over again.

Becoming a mentally tough runner

As far as Fitzgerald is concerned, if you want to become a mentally tough runner, then you’re halfway there. “The rest is just figuring out the details.”

“Some athletes are willing and able to suffer more than others, and only those who are willing to suffer the most realize their fully potential in races. Remember, running performance is ultimately limited by perception of effort and not by fitness, which merely constrains performance.” – Matt Fitzgerald

Something I really related to in this book was the chapter that discussed strategies for emotional self-regulation. For most of us, running close to our limit tends to produce negative emotions, which can have an impact on performance.

Fitzgerald talks about using acceptance as a strategy to cope with the discomfort you feel when emptying the tank during a race.

“This entails making peace with, or being okay with discomfort. You’re not trying to persuade yourself that you’re not really uncomfortable- that doesn’t work. Rather you’re accepting your discomfort as a necessary part of the task you’re performing. You can’t control how you feel when you’re running, but you can control how you feel about how you feel…” he says.

When determining pacing goals for a race, we should consider pace first and time second. You can do this by using benchmark workouts to define what that means for you as an athlete. (There are several examples in the book for 5K up to marathon distance.)

Then, we have to consider outside influences, like course, terrain, and weather conditions.

Finally, Fitzgerald cautions against being afraid to make a mistake. It’s ok to make a mistake! That’s how we learn, but we have to make a conscious effort to do better the next time, not just repeat the same mistake over and over again.

Special Pacing Challenges

Remember how Fitzgerald talked about our tendency to rely on devices to do the pacing for us? Well, he has a few “pacing challenges” to help you better develop that ability.

I really liked an exercise called precision splitting, which is something you can do with a set of intervals like 8 x 400m or 6 x 800m. The first option is to pick a target time and aim to nail each interval perfectly. The second option is to run the first interval by feel, capture the time, and aim to hit each subsequent rep. (I like this method best).

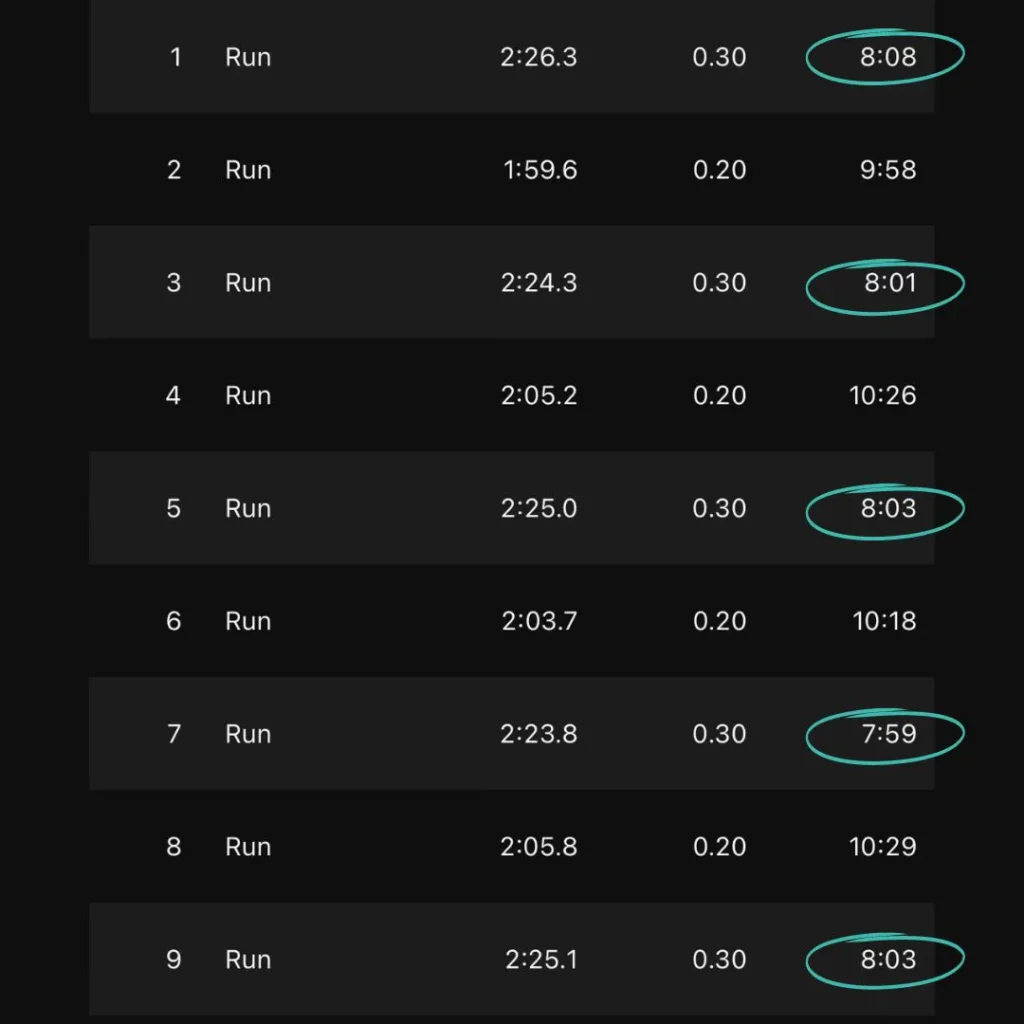

I tried this today during a 30-minute brick run my coach had planned. I was supposed to do six .30 intervals in a specific pace range. So, I ran the first one, looked at my watch, and tried to think about what the effort felt like. Then, I ran the remaining five intervals without looking at my watch and tried to maintain the same pace…

I wasn’t sure how this was going to go, but I was pleasantly surprised by the result!

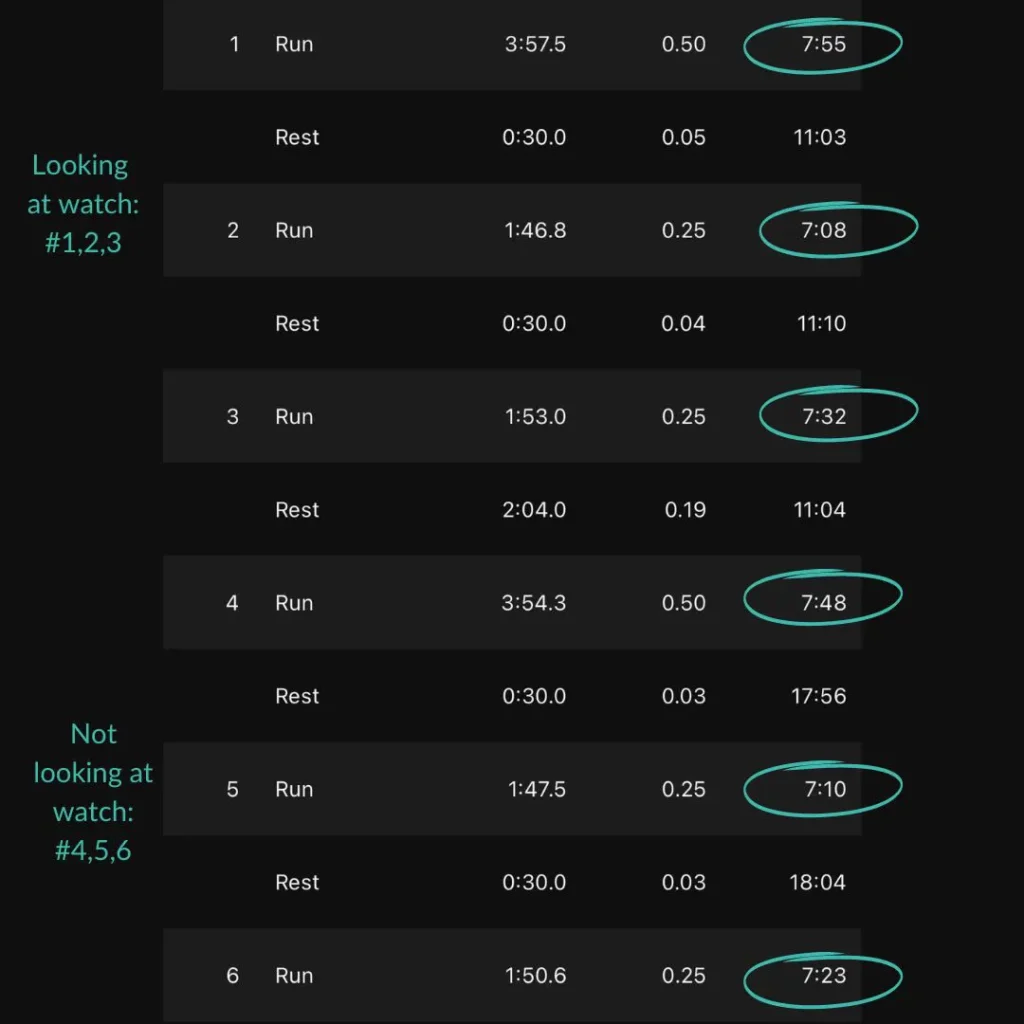

I did my own version of this exercise during another brick run my coach had planned this week. This one was a bit harder because I had three different paces to hit during a single run: above 5K, under 5K, and at 5K. This is more of a challenge for me because I often have a hard time distinguishing between “fast paces,” so “easy fast,” “medium fast,” and “fast fast.”

For the first three intervals, I looked at my watch to get the feel of each pace. Then, for the second set of intervals, I tried to hit each based on how I thought it should feel, without looking at my watch. I was super proud that I actually did it!

There’s another exercise called long accelerations where you run for a set period of time- 3, 6, or 11 minutes, and the goal is to continuously accelerate to the end. So you can’t slow down and you can’t plateau. Also, you can’t look at your watch…

This one seems very hard, but I’ll have to try it one of these days.

“Mastering pacing is not about learning how to run completely by feel, paying no attention to numbers. It’s about finding your limit, which requires a fine calibration of subjective perceptions against objective measurement.”- Matt Fitzgerald

Even if you aren’t doing speed work, paying closer attention to pace, distance, and time is something you can do on long, easy runs too. During my 8-mile run last weekend, every time my watch clicked over at a mile I would start an internal timer and see if I could estimate how far I’d run.

So, I would say, “Ok, I think I’m at .40, and I’d check my watch and see .48.”

It was a fun exercise and helped to keep my mind focused instead of daydreaming, which I’m prone to do on long, easy runs…

Q&A with Matt Fitzgerald

Brittany- Why did you want to write this book?

Matt- “As a coach, I used to view my job as training an athlete to go race. But what I’ve found is that really good preparation is no guarantee of a really good race. You have to execute the race. Certainly if training has gone well and you’re fit enough to achieve your goal, that’s necessary to success, but that’s not sufficient.”

Brittany- Tell us briefly about your athletic background.

Matt- “I started running in 1983, when I was 11, and did my first triathlon in 1998.”

Brittany- How many books have you written or collaborated on? What’s your favorite?

Matt- “35 and the short list would be Iron War, Life is a Marathon, and Running the Dream.”

Brittany- Why do you think athletes are so bad at pacing?

Matt- “Every athlete gets better at pacing with experience, but you get better faster if you reflect on your experiences. I think a mistake runners make, and one of the reasons I wrote the book, is pacing skill development has to be a conscious priority. What a lot of runners do is race and then make the same mistakes they made in the last race. They kick themselves and say they’ll do better next time in the vague hope that things will change. I want you to stop repeating the same errors in pacing. You need to consciously and pragmatically work on your pacing. Most runners can’t really say they’re doing this. They just know they need to get better.”

Brittany- Why is it sometimes easier to keep a steady pace throughout, rather than gradually negative split (getting faster as the race goes on)?

Matt- “Part of it is that there are individual racing styles. Some general rules of effective pacing apply to every athlete, but there’s still room for individuality. Some athletes like to push the pace at the front, while some sit and then kick at the end. One thing I’ve noticed about myself is that I don’t like running side-by-side with people. I like to pass, or you pass me. You need to give yourself permission to express your own style while respecting the principles of good pacing.”

Brittany- This book primarily talks about pacing a running race. Are there different considerations triathletes need to take into account?

Matt- “It’s certainly different and some of the science about pacing a triathlon is really interesting. I can’t say that it’s all been answered or that it’s something you can reduce to a formula. It does depend a bit on the distance of the race: a sprint is very different from a full Ironman. It also depends on the level of athlete and your relative strength and weakness in the three disciplines.”

So let’s say a 70.3 is a 5 ½ hour race for an athlete. That 5 ½ hours is divided among three disciplines, which makes the pacing for that effort different than if it was one discipline that lasted 5 ½ hours. Let’s say the swim takes 35 minutes. 30 minutes into the swim, that athlete should be working really hard, whereas if they were doing a 5 ½ hour swim, they shouldn’t.

In total, the event duration is exactly the same, but it’s not just one discipline. You’re kind of splitting the race, not thinking of it as a whole, but three races with three distinct finish lines. What the research has shown is that it’s fine, if you’re well prepared, to almost empty the tank in the swim, almost in the bike, and then empty it for the run. It’s a balancing act, but that’s part of what makes triathlon so cool. It’s more complex.”

Brittany- Can you talk about developing a pacing plan for a race and how this might look different for different types of athletes?

Matt- “Athletes and coaches need to be pragmatists. You need to know what works for you. If not planning enough seems to be holding you back, like it’s too loosy goosy, and you’re just winging it, then go in the direction of becoming more analytical. If you tend to be an overthinker and get in your own way, then do less. A plan is really just an educated guess. Be pragmatic. The goal is to empty the tank. Think, ‘What do I need for me to do that at this stage in my development as an athlete?’”

Brittany- This idea of emptying the tank is a hard concept to grasp. Can you explain how people can go about doing that?

Matt- “In competition, I define pacing as the art of finding your limit. That’s what you’re trying to do. When you cross the finish line and look back at the race you just completed, you want to be able to say there’s nothing I possibly could’ve done any different that could’ve gotten me to the finish line faster. If you can say that, you’ve found your limit.

One of the things that makes it hard is the closer you get to your limit, in any type of endurance race, the more discomfort you experience. It’s extremely unpleasant to find your limit. There are some pretty deep instincts that reject embracing that level of discomfort. Some people are a bit more comfortable being uncomfortable. That’s what you’re up against. There’s internal regulation in all of us. It’s about getting to a point where you accept the discomfort that’s unavoidable.”

Brittany- Can you talk a bit about our over reliance on technology and how that can be damaging to our pacing ability?

Matt- “I’ve defined pacing as it relates to competition as the art of finding your limit, so your limit in endurance racing is perception. It’s not physical. We have physical limits, but we don’t encounter them directly during a race.

If you’re 20 miles into the bike leg of a 70.3, and I ask you if you can speed up, you would say of course. If I see you again at 40 miles, could you go faster at that point? Yes, even though you’re deeper into the race. If you’re doing it right, the only time you’re going to say no you can’t go any faster is when you’re literally in sight of the finish line.

Endurance racing isn’t power lifting or sprinting- full gas for a short period of time. All you’re doing is holding yourself back, so we don’t really touch our limits. The discomfort is something that keeps us from the limit, and very often, almost always, we reach our psychological limit before we hit a hard physical limit. So if the limit is a feeling, then how the hell is a watch going to tell you how to get to that limit?”

Brittany- Are you working on any new projects?

Matt- “I’m working on something now about my journey through long COVID. At midnight on January 1st, I registered for the Javelina 100K ultra in Arizona, even though I was completely unable to run at the time. The book is called ‘Dying to Run,’ and it will chronicle the experience of losing my health and athletic identity. It’s meant to be a story about the trauma we all experience. Hopefully, by sharing my story, it might help others heal from their trauma in the aftermath of the pandemic.”

If you want to buy Matt’s book- How to Run the Perfect Race, you can find it on Amazon.

I have 4 more books from incredible authors to review for the blog, so stay tuned…